Project Blog

9 October 2025 – Intro to Wwise and Mars

I had a class this last week introducing audio middleware, specifically Wwise. I was given the choice of two games for my sound for games project, one student made and set on Mars, and the other a sample version of the game ‘Cube’ that AudioKinetic use for their certification, based on a magic world with the player as a ‘wwizard’. With the networking opportunities of working on a student made game and the spacey/technological vibe of the game ‘Mars’ itself spoke to me, so I’ve chosen to work on ‘Mars’. The general atmosphere and sound effects that instantly popped into my head when I was introduced to the game via gameplay demo in-class made it easier to plan out how exactly I would go about this project.

With this introduction to audio middleware came an introduction to triggers, game calls and events. Luckily, I have a spreadsheet detailing the connections all these have with each sound or change in music, making it significantly more concise and easier to understand from a musician’s perspective. However my own experience in computing science education, even if a small amount, still has helped in understanding the bits of logic based coding that is needed.

The gameplay itself of ‘Mars’ has only one level for now, with exploration of the barren landscape and combat between three different enemy types – well, two different and a larger boss version of one of the types. This project will not only characterise each movement and the general ambience with sound effects, but have composed dynamic music to interchange between the states the player character goes through, in solo exploration, in combat and anywhere between the two.

The use of dynamic music in games has been a topic of interest to me for a while, so seeing and learning how it is done through this project is something I am incredibly excited to be doing.

18 October 2025 – Sound Design and Dynamic Music

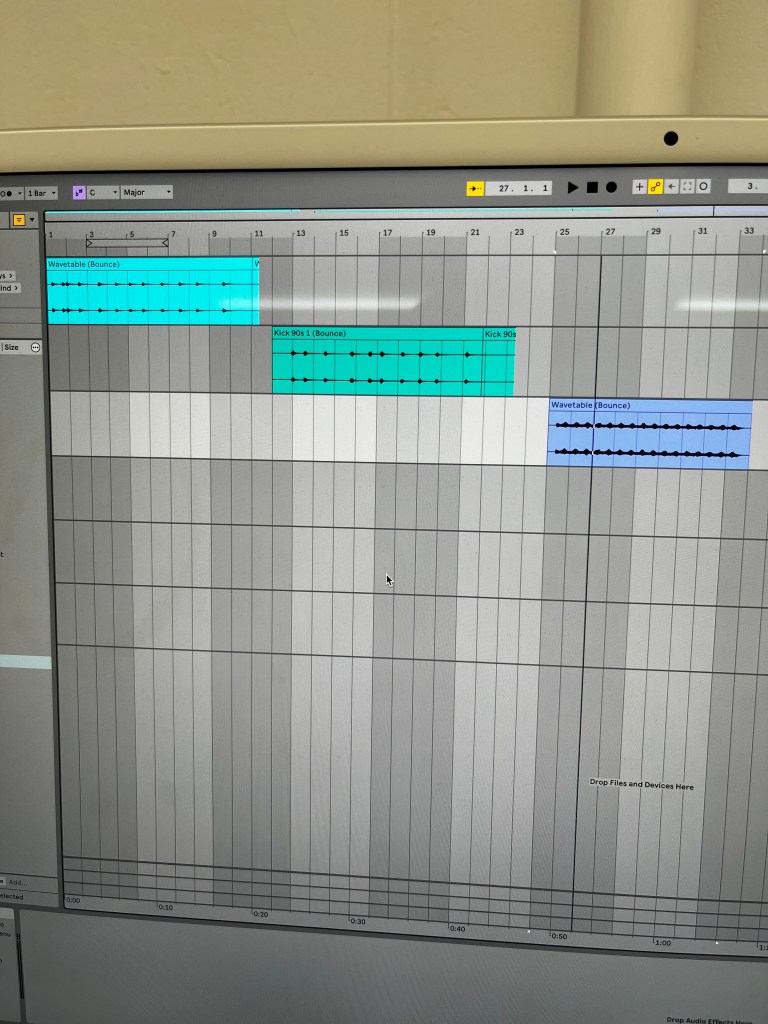

I decided on using Ableton for any sound synthesis work for this project as that is what I personally know how to use best. Flipping between actively playing ‘Mars’ on one window and tweaking sounds on the other is a genuinely fun experience. Having to think on how objects should act and be portrayed with sound then implementing that either from scratch with wavetable or operator, or by taking sounds on sound libraries and changing them to fit ‘Mars’. Using delays to provide a sense of pulsating for laser blasts and other such effects to flesh out the world and materials the player interacts with.

When it comes to regular composing, each event can be written in fixed time. Dynamic music in games doesn’t allow for this as a player can choose when events on-screen happen and the music must follow that at all times, the music must follow the drama and suspense of the player’s actions rather than creating its own. Instead of one large climax at 2/3rds of the piece, the player may decide to run away from the action to heal, as such the music may dissipate in drama before they return to action.

In class, the techniques for creating adaptive music were shown. Reorchestration is the use of many stems layered on top of one another, usually swapped with other similar stems using random choice or in sequence to build drama. This technique provides a lot of variation with how many permutations of stems that could be played at any given time. The other technique uses fully composed ‘sections’ of music that can be shuffled around, this is called resequencing. Both of these could be rearranged and changed based on time or player action.

I believe a mix of both for differing moods within the game (in terms of ‘Mars’, the difference in exploration and combat) is good for either building tension or ambiguity.

24 October 2025 – Implementation in Wwise

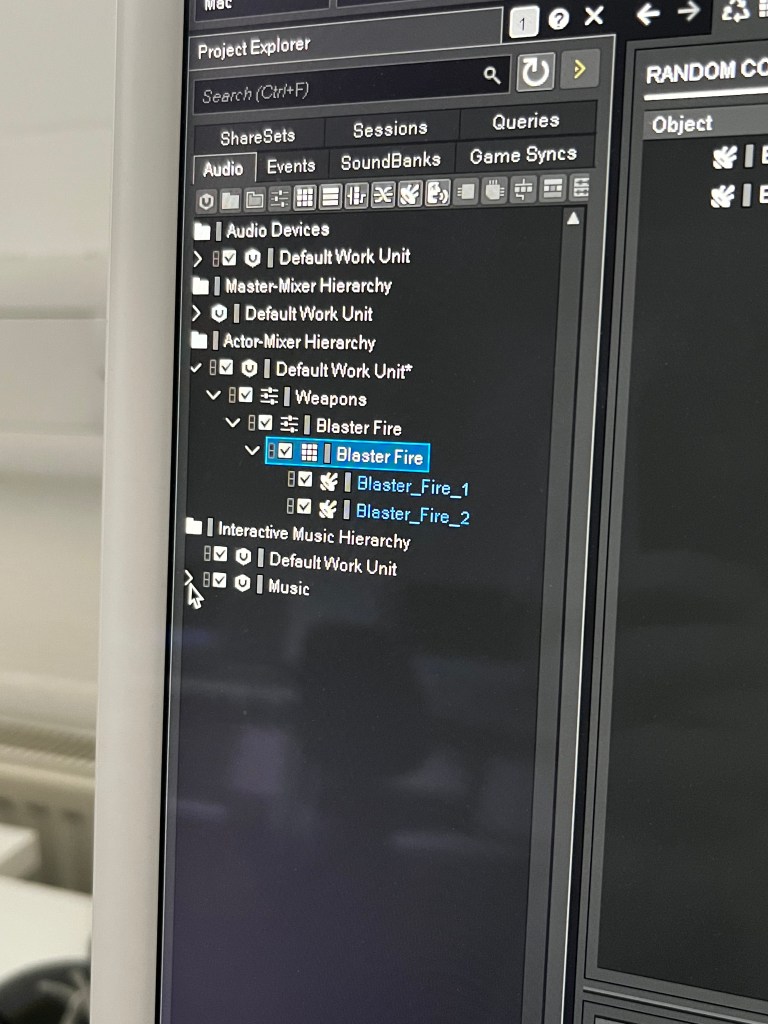

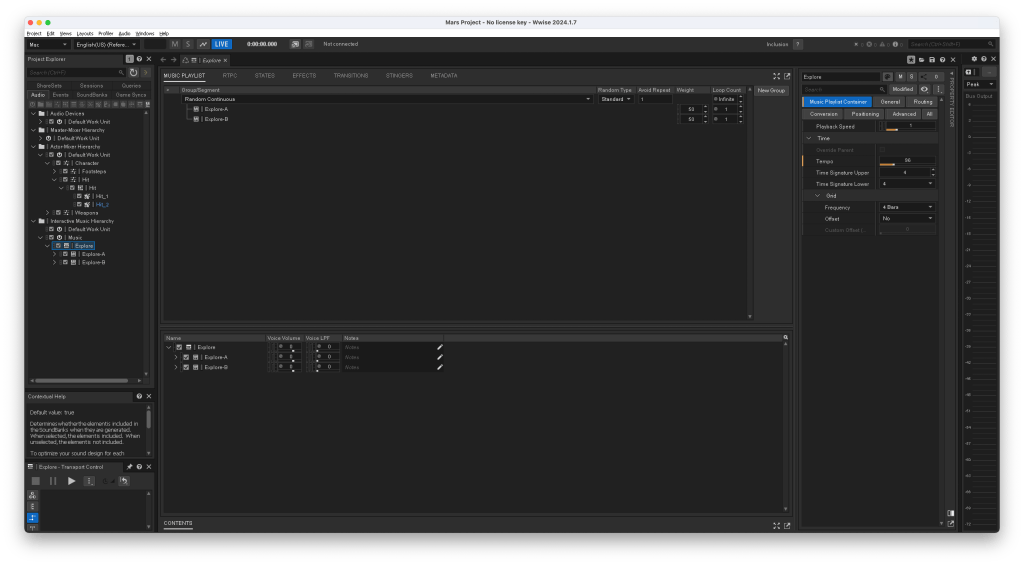

Implementing your various sound effects and music segments (or tracks) into your game through Wwise is done via ‘hierarchies’ depending on the type of sound.

Shown here is the start of my own implementation for ‘Mars’ where the Master-mixer, Actor-mixer and Interactive music hierarchies are viewed.

All sound effects that relate to objects in the game world (practically all diegetic sounds) are places within the Actor-mixer hierarchy. However, the sounds are not just inputted straight into it. First a work unit is created, then descending ‘actor-mixers’ that act mostly as groups to section similar sounds, or sounds that happen by the same trigger(s). Within these ‘actor-mixers’ are containers, these determine the order of the sounds in them. Random containers will play the sounds in them randomly (however each sound can have a different ‘weight’ that can ensure they are chosen more/less frequently if needed). Sequence containers will play the sounds in order that they are shown in Wwise.

The Master-mixer hierarchy is primarily used as Wwise’s own mixing desk, with faders, LFOs and more. Usual mixing utilities are much needed due to the sheer number of sounds that can be played at any given time, so having the ability to auto-duck less important sounds (such as the music) to a level where the important alerting sound effects can be heard clearly is great. This also includes real time parameter controls (RTPCs) which allow you to change a sound’s parameters based off in-game events, for instance the player’s health getting low can be indicated by an increase of a LPF depending on how close to losing they are.

My personal favourite part as a musician is the Interactive music hierarchy. As stated in my last post, dynamic music can be played by full segments that are played in sequence or randomly, or by reshuffling specific music tracks. This is done similarly (in both cases) to how the Actor-mixer hierarchy is able to have random and sequence containers inside it to decide in what order similar sounds should be played. With reorchestration this is done in each track, determining which to play, if any. Whereas in resequencing this is done as a ‘list’ of full music segments that can be in sequence or random, or a mixture of both.

02 November 2025 – Composing for Mars

When composing dynamic music for video games (and other forms of visual media) it is a good idea to solidify three general ‘principles’ or moods that the sound should incapsulate. These principles can, and are encouraged to be, subjective to the composer (as long as one has not been told otherwise by a wider team). For example, my work on ‘Mars’ has been, for the most part, controlled by the principles of:

- Industrial

- Openess

- Mystery

Take the music I made for the sections of the game where the player is out exploring the world, I made sure to leave plenty of space in the sound to encourage players to explore the vast space in the game. Another example would the the choice in harmonic content, in ‘Mars’ I chose the main harmonic ‘pull’ to be a diminished chord build on the root, a dissonant chord providing a ‘mysterious’ tone while easily being able to lead that into other keys for transitions. One can think of your principles as how you see the game world, allowing for the music to cleanly fit within your view (and guide players into a similar view) of the world.

Below is an excerpt of the explore music.

These principles can also be attributed to the sound effects. For example, I thought the robotic enemies in ‘Mars’ could be somewhat rustic and clanky, like older industrial machinery that has been in the open for too long. My sound design and editing can follow this principle, with battered gear crunches and high low-frequency content for powerful, yet slightly sluggish, movements.

I have found that introducing this technique into your sound work for games not only provides a clear goal for the composer/sound designer/implementer, but also allows those that work on the sound to imply their own takes on the visual world and story, providing the sense of creativity that most musicians and artists crave.

05 November 2025 – Promoting a Project

Depending on the exact type of project you are working on, there are many different ways to promote it. This can be done after you have the finished product or while it is still in development. Promotion mainly relies on content that you take from any part of the product itself. Content can include:

- Blogs/websites (such as this one)

- Clips of the development process

- Clips from performances

- Excerpts of the work itself

- Documentaries

- Demonstrations (demos)

- Etc.

These can be interchangeable/used in conjunction (for example a documentary could include clips of the development process). The more content you take during the project the easier it will be to create promotional material once at that stage.

To put this into context, my friend and classmate Daniel Cafferkey and I produced a short documentary on the process of developing sounds for ‘Mars’ (as he too is working with the same materials I am). This small documentary shows the silent ‘before’ shot of the game, an explanation/walkthrough of the tools and techniques used in the process with clips of us using such tools and the final product shot of the game with sound (as the finished product was not finished yet we have inputted a placeholder gameplay section where the finished product segment would be). The content used to create this promotional piece included:

- Voiceover

- Gameplay recordings

- Clips of tool usage

- Excerpts of work

- Screenshots (example seen below)

With editing, these pieces of content were cut, merged together and matched with background music to create a one minute documentary.

As stated previously however, not all content has to be visual clips. This very blog and website counts as content, a public-facing piece of writing about the project that could attract visitors and possibly even people wanting to dive deeper into the project.

Do remember, your promotional material, just like your project, has its own tonal and emotional sense. You want the tone of your promotion to be consistent and purposeful.

13 November 2025 – Finished Project

With the ‘Mars’ project now finished, above is a comprehensive full demo of what I felt were the main, important sounds of note (with accompanied subtitles explaining them).

Final touches were inputted after a presentation with the ‘client’ with notes and feedback. Although there were hiccups in how the game calls were integrated that were only discovered late into implementation, I worked with what was given as best I could and worked around certain issues. A really helpful tool for any project, especially when finishing one up, is to create a spreadsheet plan of what has been completed, is close to being finished, and what is not done.

With these final touches were changes to the overall mix of certain sounds to achieve a better frequency spread across the game and clarity among sounds. I decided to EQ most sounds (for example to make the pickup voice lines stand out more) instead of using ducking or sidechain compression as I felt the sudden drop in some sound’s volume made my own personal immersion when playing the game greatly suffer. Therefore, more of a frequency based mixing technique felt more applicable.

Somewhat of a collaborative effort went into this project as although people were working separately on their own sounds and Wwise structures, any issues found within the game itself could be flagged to us all and reverse-engineered accordingly to find a fix.

This project as a whole was incredibly fun, if stressful at times due to previously unknowable bugs. Getting to learn a completely new software and new knowledge of putting music to games is now a skill I can take into further projects.